A “war of experts”: revisiting the infamous 19th century Flores Street poisonings

[ad_1]

Ricardo Jorge Dinis-Oliveira, 2019

On January 2, 1890, a Portuguese man named Jose Antonio Sampaio, Jr., died in terrible agony while staying at the Grand Hotel de Paris in Porto, Portugal. The son of a wealthy and highly respected linen merchant, Sampaio Jr. showed signs of poisoning in his final hours, including blood in his vomit. He was attended by his brother-in-law, a physician named Vicente Urbino de Freitas.

Sampaio Jr. was nonetheless buried without incident, and the family might have grieved their loss and moved on. But in late March, Sampaio Jr.’s son and two nieces suddenly became ill after eating almonds with liquor and coconut and chocolate cakes, which had arrived at the Sampaio house on Flores Street via a mysterious package. The children’s uncle, the aforementioned de Freitas, prescribed lemon balm enemas. While the girls recovered, 12-year-old Mario Guilherme Augusto de Sampaio died in spasms and convulsions on April 2.

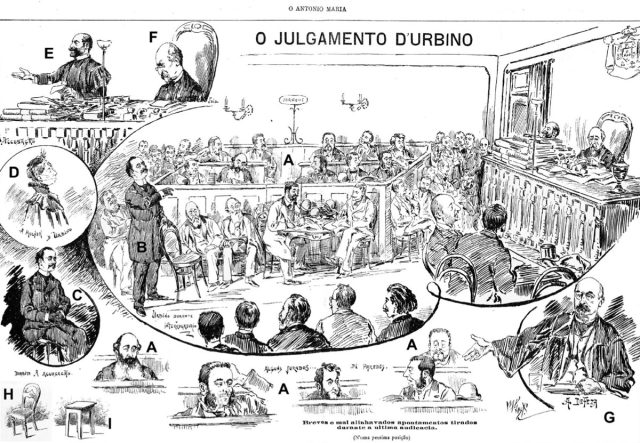

Once again, the symptoms were consistent with poisoning, and suspicion soon fell on de Freitas. He was arrested, tried, and convicted in 1893, although he maintained his innocence for the rest of his life. This was the infamous “Crime of Flores Street” and it made headlines around the world. The case continues to fascinate Ricardo Jorge Dinis-Oliveira, a forensic toxicologist at the University of Porto, more than 130 years later, because it gave birth to forensic toxicology studies in Portugal and still informs present-day Portuguese medico-legal procedures. It’s also one hell of a story: “It will certainly make a good movie,” Dinis-Oliveira wrote.

Dinis-Oliveira has spent the last 14 years poring over historical works, trial transcripts, and newspaper accounts from all over the world, even interviewing living relatives of the main characters. He compiled his findings into three separate papers. The first, published in 2018, retold the basic facts of the case. The second, published in 2019, analyzed all the relevant and contradictory testimonial evidence from the trial. Dinis-Oliveira then reviewed the contradictory toxicological evidence in a third paper published in May 2021 in Forensic Sciences Research, defending the professional reputations of his 19th century compatriots.

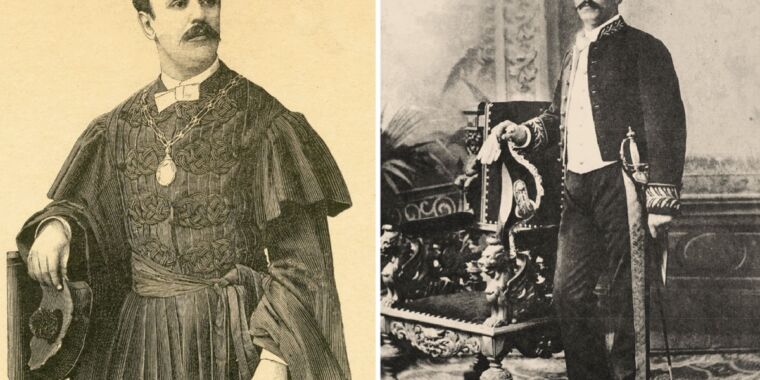

Two mysterious deaths

Born on Flores Street in Porto in 1849, de Freitas married Maria das Dores Basto Sampaio in 1877, the same year ha became a lecturer at the Medical-Surgical School of Porto. He gained professional distinction over the years with notable studies on dermatology, particularly the treatment of leprosy and syphilis. Perhaps de Freitas hoped to one day inherit his in-laws’ considerable wealth. Standing in his way were the couple’s three children—an eldest son, Guilherme, who died young; a daughter; and the aforementioned Sampaio Jr.—as well as the three grandchildren.

R.J. Dinis-Oliveira, 2018

Sampaio Jr.’s wife died young, leaving him with two small daughters. The girls lived with their grandparents while their father became something of an itinerant bohemian, much to his father’s disapproval. He took up with an Englishwoman named Lothie Karter, whom he had net at a nightclub in Lisbon. Sampaio Jr. often complained of stomach and liver ailments. He received a mysterious package in October 1898 while still in Lisbon, containing vials purportedly holding medicines to treat those ailments. Not recognizing the sender, Sampaio Jr. did not take the remedies, telling Karter he suspected it was prussic acid (a strong poison).

In December 1889, Sampaio Jr. and Karter returned to Porto and moved into the Grand Hotel de Paris. On December 28, Sampaio Jr. had lunch with de Freitas, and became ill the following day. While he initially assumed it was a cold, his condition worsened, and de Freitas was called in to consult. De Freitas gave his brother-in-law a shot of what he said was pilocarpine (now a common treatment for glaucoma).

Sampaio Jr. soon became delirious, sweating and shaking, with fever, loss of vision, and vomiting, among other symptoms. Nonetheless, de Freitas insisted on giving him a second injection. As Sampaio Jr. continued to worsen, de Freitas prescribed one last injection of pilocarpine on the afternoon of January 2, mixing the tincture himself with his back to others in the room. He asked another doctor to administer the shot.

The injection site soon developed a nasty black spot. Sampaio Jr. began vomiting violently, and finally died around 6 PM. Before he did so, he told Karter that he was convinced it was the shots of pilocarpine that had sickened him. De Freitas insisted on disposing of the vomit. When the hotelier expressed regret that the man had died so young, de Freitas allegedly told him that his brother-in-law had been “a madman, a scoundrel, who shamed the family,” adding, “Didn’t you notice the evidence of mental illness? His whole family is like this. They all die by the same way.”

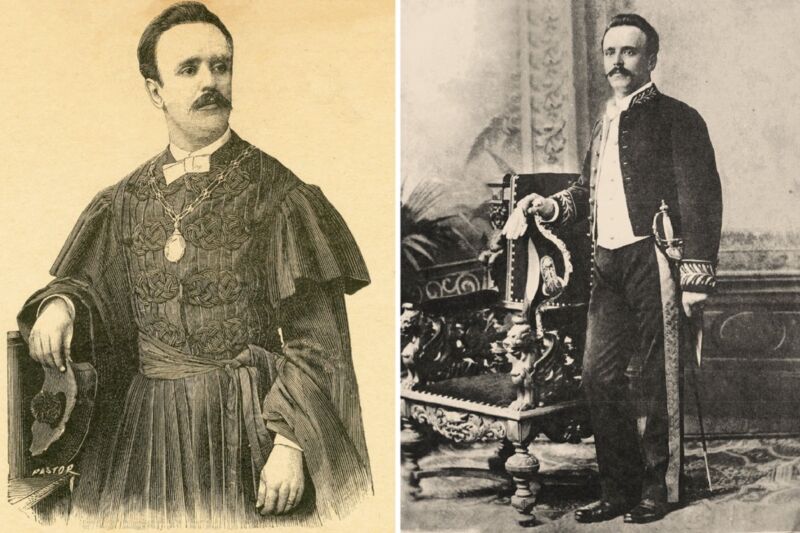

R.J. Dinis-Oliveira, 2019

Then the three young children fell ill, with 12-year-old Mario experiencing convulsions and eventually falling into a coma and dying. The two girls had similar but less severe symptoms—perhaps because they had eaten less of the almonds and cakes. One of the doctors called in to consult thought poisoning seemed likely, perhaps by opium or belladonna.

In light of young Mario’s suspicious death, the remains of Sampaio Jr. were exhumed so an autopsy could be performed. However, the body was in such an advanced state of decomposition after three months in the ground that it was impossible to make a determination with regard to any injury that might have led to his death, and no toxic substances were found in the liquefied remains of the man’s stomach, intestines, lungs, and heart. The same was done for the remains of Mario, and this time the experts did find evidence of lethal amounts of morphine and delphinine (two toxic plant alkaloids), as well as an opium alkaloid called narceine in the viscera and urine.

De Freitas was arrested on April 16, 1890 and charged with the murder by poisoning of Mario. There were also rumors that de Freitas had also poisoned a banker, and a rival professor at the Medical-Surgical School of Porto who had died three years earlier, although no evidence was ever produced to corroborate those rumors.

R.J. Dinis-Oliveira, 2018

Trial of the century

The prosecution assembled a fairly damning case. The police investigation revealed that de Freitas had bought a box of almonds and chocolate cookies during a March 1890 visit to Lisbon; the confectionery clerk recognized him. The doorman of the Lisbon hotel where de Freitas was staying testified that the physician had asked where he could buy almonds for his “fiancee.” He then allegedly posed as a man named Eduardo Motta, and convinced a merchant he met on the train to mail the package to his in-laws’ home in Porto, apparently to give himself an alibi. At trial, the merchant identified de Freitas as the man he knew as Motta.

De Freitas himself agreed that his nephew had been poisoned, “but there was no crime.” He claimed a “double” had asked the merchant to mail the package of sweets. De Freitas said he had gone to Lisbon to rendezvous with a married woman on March 6, returning the same day. He went back to Lisbon on March 7-8, supposedly consulting with a close friend and colleague, Francisco Adolfo Coelho, about a medical translation. Coelho denied this visit at trial, however, and testified that de Freitas had actually written to him asking him to lie about it should he be questioned by police. (He even saved the letter.)

Certainly de Freitas’s grieving mother-in-law, Maria Carolina Basta Sampaio, was convinced of his guilt. She testified that de Freitas had asked her to lie about his treating and prescribing the enema treatments for the children, as well as trying to cast suspicion on a maternal uncle who lived in Lisbon. But de Freitas’ wife, Maria, remained devoted and loyal throughout the trial, sobbing and fainting when the guilty verdict was read.

De Freitas was sentenced to eight years in prison in Lisbon, followed by 20 years of exile. His son, Urbino Emilio Basto de Sampaio de Freitas, committed suicide in shame over his father’s conviction. While Maria’s family offered her family a pension, given their loss of income, she rejected the offer. De Freitas finally returned to Portugal in 1913, intent on proving his innocence, but he died of pneumonia shortly thereafter, still waiting for a judicial review. Maria de Freitas lived another 43 years, dying in 1956 at the age of 97.

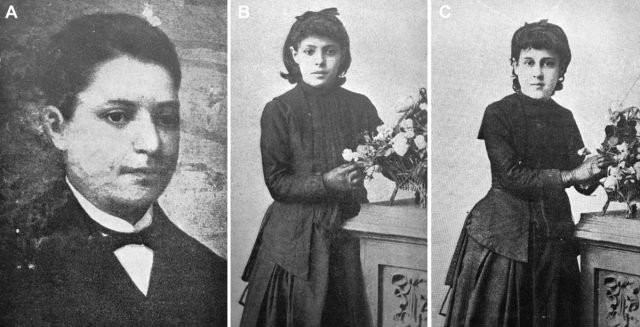

R.J. Dinis-Oliveira, 2021

The verdict was not unanimous, however, so not all jurors were convinced that de Freitas was guilty. Some of the witness testimony was contradictory, particularly with regard to whether de Freitas was in Lisbon or Porto on the key date of March 28. Also, the public prosecutor had been a former (unsuccessful) suitor of de Freitas’ wife, raising the possibility that he was motivated by personal animosity toward the defendant. Finally, there was considerably controversy over the various toxicological reports.

War of the Experts

Was de Freitas a “monster” who was truly guilty of murder, or a martyr to an overzealous prosecution? It’s a question that would have a fairly straightforward answer today given modern toxicological methods, according to Dinis-Oliveira. But back in the late 19th century, “the unmistakable detection of morphine, narceine, and delphinine seems somewhat very difficult in light of the scientific advances of the time,” Dinis-Oliveiras wrote in his 2018 paper.

The expert evidence presented at trial was questioned at the time by an advisory judge, who noted the lack of input from foreign toxicologists. So several foreign experts were also invited to weigh in, including Louis Lewin, who pioneered the study of psychoactive plants. Unfortunately, “All these consultations were unfavorable to the work and conclusions of the official experts, extensively highlighting the (“inexcusable”) errors and the presence of putrefaction products that were allegedly confused with toxic plant alkaloids, as well as the abuse and misunderstanding of the use of analytical methods,” Dinis-Oliveiras wrote in his 2021 paper. Several rebutted the finding of morphine and delphinine in Mario’s viscera and vomit.

R.J. Dinis-Oliveira, 2021

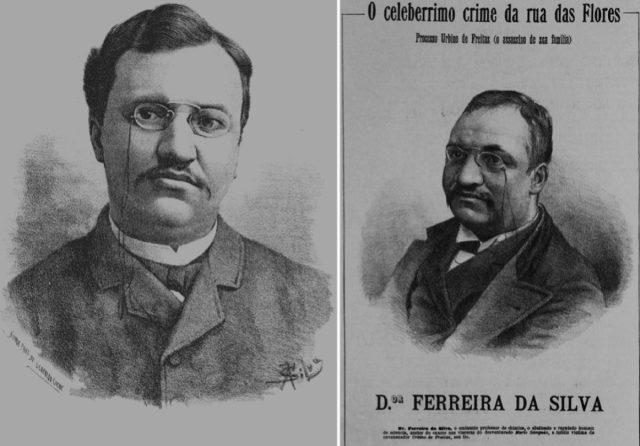

Dinis-Oliveiras takes issue with this characterization of the Portuguese experts’ work. Much of this latest paper focuses on the work of Antonio Joaquim Ferreira da Silva, who was “practically chained” to his laboratory for the three years between de Freitas’ arrest and trial. (His analysis also concluded that young Mario Sampaio had died of morphine and delphinine poisoning.) Da Silva made several discoveries over the course of that research, per Dinis-Oliveiras, including characterizing new reactions to detect cocaine, serine, and the alkaloids, as well as eserine. Some of these discoveries were presented by his peers at the Paris Academy of Sciences.

All of this shows that da Silva “did not act lightly, but worked with the forthrightness of a good toxicology expert,” Dinis-Oliveiras wrote, despite being relentlessly attacked and having his scientific reputation questioned throughout the trial. In fact, da Silva’s diligence “inaugurated a new phase of toxicology and forensic chemistry in Portugal.” Dinis-Oliveiras concludes, “The experts of Porto did a remarkable job that was nearly impossible to rebut considering the knowledge of that time.”

Without that toxicological evidence, it is unlikely that de Freitas would have been convicted, according to Dinis-Oliveiras. He suggests that even more insight could be gleaned if the remains of at least one supposed victim could be identified. The good news is that Dinis-Oliveiras finally tracked down the location of the corpse of Sampaio Jr. in 2020, and was able to perform a new autopsy. DNA analysis to confirm the corpse’s identity, and toxicological analysis testing for morphine, delphinine, or narceine, is underway. The results will be reported in a future paper.

DOI: Forensic Sciences Research, 2021. 10.1080/20961790.2021.1898079 (About DOIs).

DOI: Forensic Sciences Research, 2019. 10.1080/20961790.2019.1682218 (About DOIs).

DOI: Forensic Sciences Research, 2018. 10.1080/20961790.2018.1534538 (About DOIs).

[ad_2]

Source link