Intrepid brewer risks scalding to recreate recipe for long-lost medieval mead

[ad_1]

Ah, mead, that sweet, honeyed alcoholic beverage that has been a staple at Renaissance Fairs for decades (along with giant turkey legs). It’s also increasingly popular among home craft brewers since it’s relatively easy to make. Those in search of a unique challenge, however, are turning to a special kind of medieval mead called bochet. The only known detailed recipe for bochet dates back to the late 14th century and was lost for centuries, until it was rediscovered around 2009.

Fermentation in general has been around for millennia, and mead (“fermented honey drink”) in particular was brewed throughout ancient Europe, Africa, and Asia. Perhaps the earliest known reference to such a beverage (soma) is found in a sacred Vedic book called the Rigveda, circa 1700-1100 BCE. Mead was the drink of choice in ancient Greece; Danish warriors in the Old English epic poem Beowulf cavort in King Hrothgar’s mead hall; the Welsh bard Taliesin (circa 550 CE) is credited with composing a “Song of Mead”; and mead features heavily in Norse mythology.

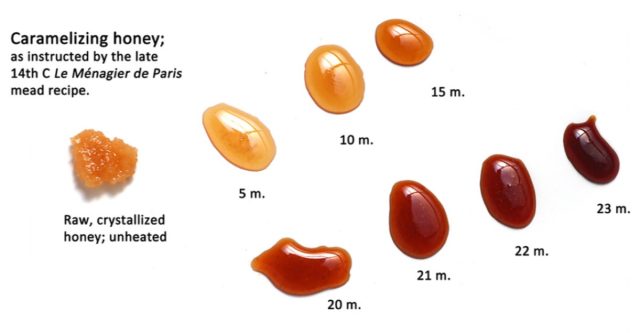

There are many different varieties of mead from all over the world. But bochet is a special variety because it calls for caramelized honey; additional spices are optional. This makes it attractive to craft brewers looking for something a little bit different—brewers like Gemma Tarlach, who recently detailed her experiments making bochet in a fascinating article for Atlas Obscura.

Tarlach was keen to be as historically accurate as possible, and while researching, came across a 2020 paper by independent researcher Susan Verlag. Verlag is a beekeeper and mead maker interested in recreating historic beverages, taking the appropriate historical context into account. “The modern recreations of historic beverages often seems influenced more by poplar assumption than by historic scholarship,” Verlag wrote in her paper.

iStock/Getty Images

Verlag found the earliest complete recipe for bochet in a 1393 French collection of recipes, Le Menagier de Paris. That recipe began circulating widely among craft brewers after the 2009 publication of The Good Wife’s Guide: a Medieval Household Book, a translation of the original treatise. Here are the translated instructions, per Verberg’s paper:

Bochet. To make 6 septiers of bochet, take 6 quarts of fine, mild honey and put it in a cauldron on the fire to boil. Keep stirring until it stops swelling and it has bubbles like small blisters that burst, giving off a little blackish steam. Then add 7 septiers of water and boil until it all reduces to 6 septiers, stirring constantly. Put it in a tub to cool to lukewarm, and strain through a cloth. Decant into a keg and add one pint of brewer’s yeast, for that is what makes it piquant—although if you use bread leaven, the flavor is just as good, but the color will be paler. Cover well and warmly so that it ferments. And for an even better version, add an ounce of ginger, long pepper, grains of paradise, and cloves in equal amounts, except for the cloves of which there should be less; put them in a linen bag and toss into the keg. Two or three days later, when the bochet smells spicy and is tangy enough, remove the spice sachet, wring it out, and put it in another barrel you have underway. Thus you can reuse these spices up to 3 or 4 times (Greco and Rose, 2009, p.325).

According to Verberg, most of the bochet being brewed today follows this basic recipe, although she cites a handful of other recipes dating from 1385 to 1725 that are a vaguer as to whether caramelized honey (or even fermentation) is required. Verberg suggests that the medieval definition of what constituted a true bochet was far less rigid than how it is currently defined: as a mead flavored with caramelized honey.

“The defining features of an historic bochet are it is made by boiling sweetened water with spices and letting the concoction slowly cool down, infusing into a wonderful tasty beverage,” she wrote, adding that based on her research, “It is likely the beverage evolved throughout the ages from an alcoholic spiced honey drink to a non-alcoholic sweetened and spiced tisane.”

Susan Verberg, EXARC Journal, 2020

One of the first things Gemma Tarlach did while conducting her own bochet experiments was to answer the burning question: what the heck is a “septier”? She dug through Parisian archives and concluded that a septier is roughly equivalent to about four gallons. If one follows the 1393 recipe, that translates into a honey-to-water ratio of one quart of honey (about three pounds) to four pounds of water. However, “Most modern interpretations call for a ratio of 3-4 pounds of honey per gallon of water,” she wrote—four times the honey as the 1393 version.

Tarlach had easy access to raw honey, since she is also a beekeeper. From Verlag, she learned that medieval mead makers didn’t extract the honey from the wax comb the way beekeepers do today. Instead, they crushed the comb, which meant that medieval honey contained both beeswax and a few squished bees. So that’s what Terlach did, using the comb of a dead colony.

It was also challenging to find historically appropriate yeast for the fermentation. Most modern mead makers use commercial wine yeast, per Tarlach, but the 1393 recipe called for beer or bread yeast. Tarlach opted for several different commercial ale-brewing yeasts for her experimental batches, along with one batch using a white wine yeast variety, plus a batch using wild yeast. Instead of using a lab-derived nutrient powder to kick-start the yeast, she added a few organic raisins, reasoning that medieval mead makers would have had access to dried fruit.

The caramelization process is the trickiest step. You need a very large stock pot (unless you happen to have a very large cauldron at hand), since honey can double or even triple in volume when it’s heated. Screw up the process, and you might end up burned by a “sugar volcano” when the honey concoction explodes. And since boiling sugar adheres to the skin (unlike boiling water), those burns can be severe. It’s also important not to lean over the pot once the honey starts bubbling, as this can scald your eyeballs.

Bochet needs to age for about a year, so the final verdict won’t be pronounced until then. But Tarlach proclaimed her experiments a success after sampling some of the month-old batches while she was transferring them to new jars:

They were thinner in body and less sweet than other meads I’ve made, thanks to the lower ratio of honey-to-water. The different yeasts gave each micro-batch its own distinct character, from a bone-dry, astringent drink made with white wine yeast to the sweeter and smoother concoction that used English ale-style yeast. The Kveik’s dominant notes were bitter and medicinal—perhaps appropriate, since Verberg’s research suggests bochet may have been drunk to balance one’s humors. The wild yeast strain was milder overall, similar to the English ale–style but not as sweet…. All of them taste of caramel, honey, and history.

Those interested in trying their hand at their own batch of bochet can find Tarlach’s full adapted recipe here. Just be sure to use a large pot “at least three times larger than the volume of the honey” during the caramelization step, lest you end up scalded by the dreaded sugar volcano.

[ad_2]

Source link