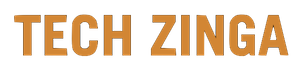

Two visionaries: Marie Curie forged a friendship with dancer Loïe Fuller

[ad_1]

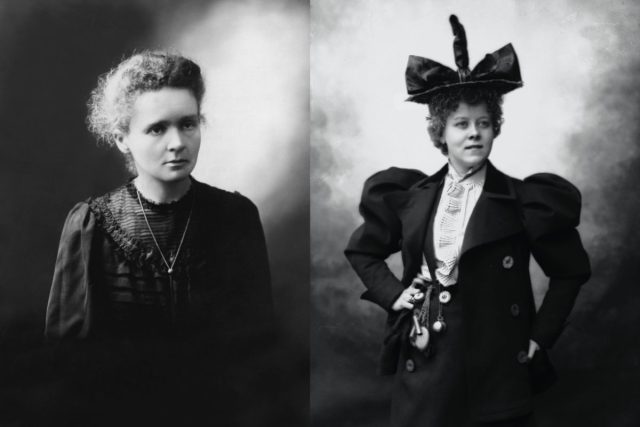

Both the arts and the sciences flourished in Paris during the years of the so-called Belle Époque at the dawn of the 20th century. This was when Nobel Prize-winning physicist Marie Curie and her husband, Pierre, made their breakthrough discoveries in radioactivity, discovering two new elements. At the same time, a modern dancer and pioneer in theatrical lighting named Loïe Fuller, who was all the rage in Paris, dreamed of incorporating radium into her stage act. Science writer and communicator Liz Heinecke brings the lives of these two visionary women together in an illuminating new biography, Radiant: The Scientist, the Dancer, and a Friendship Forged in Light.

The details of Marie Curie’s life are very well-documented and well-known. She left her native Poland and moved to Paris at 14 to pursue a degree in science, living in abject poverty while studying and conducting research. She met a chemist named Pierre Curie, and they began collaborating, eventually falling in love and getting married in 1895. The Curies had been married for six months when Wilhelm Roentgen discovered X-rays (winning the very first Nobel Prize in physics in 1901). Soon after, Henri Becquerel published his insight that uranium salts emitted rays that would fog a photographic plate in early 1896. Becquerel’s uranium rays so fascinated Marie that she made them the focus of her own research.

With Pierre, she uncovered evidence of two new elements they dubbed polonium and radium. The couple shared the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics with Becquerel for their work developing a theory of radioactivity—she was the first woman to be so honored. After Pierre’s tragic death in a 1906 street accident, Marie developed new techniques for isolating radioactive isotopes from pitchblende and eventually succeeded in isolating radium in 1910. She won a second Nobel Prize (this time in chemistry) in 1911 for the discovery of polonium and radium. She remains the only woman to win the Nobel Prize twice and the only person to do so in two different scientific fields.

People who know people

Loïe Fuller, on the other hand, has been largely relegated to the footnotes of history, although there has been a resurgence of interest in her career and influence in recent years—most notably in a featured segment during Taylor Swift’s 2018 Reputation Tour, and the work of choreographer Jody Sperling. Born in the Chicago suburbs in 1862, she was a child actress who later began choreographing and performing her own dances, usually in burlesque, vaudeville, and circus venues. She started experimenting with a long skirt, moving it in different ways to explore how it reflected light, and by 1891, she had figured out how to illuminate her silk costumes during performances with lights of different colors to create striking visual effects. She was something of a self-taught chemist, eventually patenting the use of various chemical compounds and salts to create color gel and luminescent lighting.

Fuller achieved notoriety and rave reviews with her signature “Serpentine Dance” (captured on film by the Lumière brothers in 1897, although Fuller was not the dancer featured). According to dance historian Jack Anderson, “The costume for her Serpentine Dance consisted of hundreds of yards of China silk which she let billow around her while lighting effects suggested that it was catching fire and taking shapes reminiscent of flowers, clouds, birds, and butterflies.”

Alas, other, lesser dancers soon appropriated her work for their own performances, prompting a frustrated Fuller to tour Europe in hopes of gaining more recognition for her art. Her performance at the Folies Bergère in Paris was a smashing success, and she became a regular there, performing her “Fire Dance” as well as the “Serpentine Dance.” She was a fixture of the local Art Nouveau scene, hanging out with such luminaries as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Auguste Rodin, Stéphane Mallarmé, and many other contemporary artists and writers. She was also a mentor and friend to American dancer Isadora Duncan and weathered public criticism over her decision to live openly with her lesbian partner.

Pierre and Marie Curie attended one of Fuller’s performances at the Folies Bergère and were greatly impressed. The admiration was mutual: Fuller was so captivated by the Curies’ radium experiments that she wrote to them in 1905, asking about the possibility of making a costume out of radium (she was unaware of just how limited a supply was in existence). Marie politely advised against it, although she herself liked to carry around vials of radium and enjoyed visiting the lab at night because “the glowing tubes looked like fairy lights.” Undeterred, Fuller worked fluorescent salts into a black gauze dress that she wore to perform her “Radium Dance,” creating the illusion of twinkling stars or ghostly lights surrounding her as she swirled on a darkened stage.

At first glance, the two women don’t seem to have much in common, but with Radiant, Heinecke has teased out some intriguing parallels between them as they transformed their respective fields and forged an unlikely friendship. Ars sat down with Heinecke to learn more.

Ars Technica: Marie Curie is practically a household name, but Loïe Fuller is not. So I’m curious what drove you to bring these two women together in a single book?

Liz Heinecke: I was reading Eve Curie’s biography of her mother and ran across Loïe Fuller’s name. I was an art major in college. My daughter is a theater kid, and I love watching dance, although I’m not a dancer myself. I googled Loïe Fuller and was fascinated right away. Eventually, I found the New York Public Library of Performing Arts database and discovered they had a little bit of her writing available to look at online. And I discovered that she was interested in radioactivity, that she had met Thomas Edison, that she was a friend of Auguste Rodin. She knew all these interesting people, and I hadn’t ever heard of her. She basically pioneered modern stage lighting. When I discovered that Marie and Loïe were born and died within five years of each other, I decided to write about the two of them together and have their stories intersect in parallel narratives.

Ars Technica: Marie Curie and Loïe Fuller met in person at least once, but what do you see as the binding connection between them?

Liz Heinecke: Curiosity. Loïe was an extremely curious person. Ultimately Loïe was probably the driving force in staying connected to Pierre and Marie because she really loved science. She wasn’t well-educated, but she was very smart and knew that technology was the thing that made her stand out. She went to Marie and Pierre’s labs because she was very curious about radium and radioactivity. I think Marie was curious about Loie’s world, too. We know that Marie and Pierre enjoyed art and theater and that Loïe took them to Rodin’s studio to see his work.

Both of them were far from perfect. Marie made mistakes in her life, but she was a more serious, careful person, and Loïe was just kind of out there. But I love that contrast, and I wrote them that way. I mean, if you read what Loïe wrote about Marie, she always felt she would never gossip about Marie. She always wrote, “Marie is very private. I want to respect her.” She did not care as much what people thought about her, as long as people came to her shows.

ullstein bild, Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis, via Getty

Ars Technica: You chose to write Radiant very much in the style of a novel, even though it is technically nonfiction. Why is that?

Liz Heinecke: I love a good nonfiction narrative, particularly about science. When I started thinking about the story, Loïe in particular, it’s so visual. I imagined Loïe dancing on stage. I could picture Marie and Pierre in their lab surrounded by tubes of glowing radium. So I really wanted to write it so it read more like fiction. I felt like I would be able to reach a different audience, writing a book that read more like a novel rather than a straight science narrative or a straight biography.

I state in the beginning of the book that the dialogue is invented, both internal and external. I wrote dialogue based on what I had learned about the two women. After a year reading every document I could find, I felt I almost knew them. I knew that Loïe drank black coffee and Marie drank tea, what they ate at different parts of their lives, and what they worried about. But I tried to base all the dialogue on the facts that I had uncovered. Certainly all of the scenes are based on factual events in their lives that actually happened. For instance, even if you read about Loïe Fuller, no one really talks about the fact that she danced on top of the Eiffel Tower during the summer solstice. There’s so much science involved in the Eiffel Tower, I could have written a whole book just about that one night and all the interesting people that were there.

Ars Technica: I did not know that Loïe Fuller had met with Thomas Edison. It makes sense because he was involved in cutting-edge sound and lighting as well as moving pictures, and she was interested in the scientific aspects of her art. We have had this notion that there are two cultures ever since C.P. Snow coined the term in 1959. But fundamentally, science is culture, and vice versa. Loïe Fuller kind of encapsulates that.

Liz Heinecke: She does. She was so good at bringing different technologies together and creating something new. You could almost write a parallel story about Loïe and Edison. Neither of them was very well-educated, but they were both the predecessors of today’s most popular people on social media. They were both extremely good at self-promotion. They both cultivated their images very carefully. They strike me as being very similar.

I love when different disciplines come together. I feel like society today has become so compartmentalized, and in Paris in 1900, it was sort of that way, too. The scientists mostly hung out with the scientists. I thought it was so cool that Marie Curie opened herself and her world up to this dancer—someone completely outside of her sphere. It really enriched both of their lives. I feel like that’s when you see huge explosions of creativity—when people move outside of their own spheres.

Grand Central Publishing

Ars Technica: Has writing this book inspired you to try to recapture some of that Belle Époque interdisciplinary spirit?

Liz Heinecke: There’s nothing more fun than going to the library and reading through old documents, trying to find something new that no one has discovered yet. And there are so many scientific experiments you could try at home. I’m currently writing a physics book for kids, and there’s one lab that’s about creating thin layers on glass. And I thought, “Cool, let’s try to put thin layers of gelatin on glass and color it and see if we can make slides that you could hold up [to the light],” like Loïe’s multi-colored lighting.

It’s also easy to make an electroscope, the foundational concept of the equipment that the Curies used to measure radioactivity, which gives off an electrical charge. They used a version of an electroscope to spin a mirror that would let them measure how radioactive different materials were. That’s what allowed Marie to make the first real measurements of radioactivity.

I love how people from that era were able to see things very close-up with microscopes and very far away with telescopes for the first time. They could recognize that certain things under a microscope might look like a celestial object. Loïe would take things that she had seen in a scientist’s lab or under a microscope and project it on a stage. Artists are still doing that. There’s gorgeous art that modern scientists make with their microscopes and telescopes today.

[ad_2]

Source link