What psychology of mass mobilization can tell us about the Capitol riot

[ad_1]

It’s a dark moment in American history that will not be soon forgotten. On January 6, thousands of supporters of soon-to-be-former President Donald Trump gathered for a “Stop the Steal” rally in Washington, DC, to protest the certification of the 2020 election results by Congress. Speaker after speaker pumped up the angry crowd by repeating false claims of widespread election fraud, culminating with an address by Trump himself, in which he called on his followers to “fight like hell” and march on the US Capitol. The result: frenzied rioters overran Capitol Police, smashing windows and triumphantly posing for selfies as they roamed through the evacuated building. By the time the National Guard regained control, five people were dead, including a Capitol Police officer.

As people struggled to process the horror in the immediate aftermath, Michael Bang Petersen, a Danish political scientist at Aarhus University, weighed in on Twitter with some counter-intuitive commentary. While the predominant theme among many pundits centered on the role of Trump and his enablers spreading lies about widespread voter fraud and then whipping the crowd into a frenzy during that morning’s rally, Petersen suggested that perhaps they had it backward. “Did protestors storm Congress because they followed Trump and believed his misinformation about the US election? No,” he tweeted. “They followed Trump and believed in misinformation because they wanted to storm Congress.”

Petersen’s background is in evolutionary psychology, and his research focuses on how the adaptive challenges of human evolutionary history shape the way modern citizens think about mass politics. Back in October, Petersen published a review paper in the journal Current Opinion in Psychology, making the case for his thesis that “mass mobilization”—like we saw with the Trumpian insurrectionists storming the nation’s Capitol—is not the direct result of manipulation by misinformation/wild conspiracy theories spread by a dominant leader. Rather, the paper said, those factors are vital tools for coordinating individuals who are already predisposed to conflict.

This perspective “does not necessarily imply that people do not believe in propaganda,” Petersen wrote in his paper. “But it suggests that such belief can be an effect rather than a cause of the deep need for action.” He describes a tipping point dynamic, in which a group that has coalesced around, say, Trumpism, suddenly becomes sufficiently coordinated to push it over the critical threshold into mass mobilization. In other words, a phase transition occurs, and a loose group of like-minded individuals becomes a violent mob.

Did protesters storm Congress because they followed Trump and believed his misinformation about the US election?

No.

They followed Trump and believed in misinformation because they wanted to storm Congress.

My review of the research, published in Oct: https://t.co/tLypBics57. pic.twitter.com/LNq6swvsAp

— Michael Bang Petersen (@M_B_Petersen) January 8, 2021

On the one hand, Petersen wrote, this means that “groups and societies can be stable even if they contain large minority segments of individuals who share disruptive, violent, or prejudiced views.” On the other hand, “this stability can be quickly undermined if suddenly coordination is achieved.”

Petersen’s counter-intuitive insight does not let Trump and his enablers off the hook for inciting the mob by peddling disinformation; without those elements, there would be no sudden coordination. “I think that Donald Trump is a master of human psychology,” Petersen told Ars, pointing to Trump’s 2016 campaign messaging as evidence: that the world is a dangerous place, and only he could fix it and protect America from those who wish to destroy us.

Trump was offering himself as the avatar of a strong, dominant demagogue, in keeping with Petersen’s research. As he wrote in his paper, “If followers search for the optimal leader to solve conflict-related problems of coordination, they will seek out candidates who are willing to violate normative expectations by engaging in obvious lying, and who displays a personality oriented toward conflict, even if such personalities under other circumstances would be considered unappealing.”

“I think Trump knows what he does in terms of all of the psychological buttons that he is pushing,” said Petersen. “Maybe it’s not deliberate, but he has very deep intuitions about what works, and in that sense I would find it extraordinary if he didn’t know what was going on.” We sat down with Petersen to learn more about the psychological processes underlying this kind of mass mobilization.

Ars Technica: You argue that from an evolutionary standpoint, human beings should be resistant to easy manipulation. But people do believe quite a lot of silly things, and many eagerly embrace conspiracy theories.

Michael Petersen: Evolutionary psychology [holds] that the reason why we have the brain structures that we have is that they have been adapted over human evolutionary history. From that perspective, there should be limits to the degree to which we can be manipulated by others, because ultimately, we would have been at a fitness disadvantage if some person could just come and say, “Hey, do you know the Earth is flat,” or whatever, and then we said, “Oh, really?” We know that one of the ways that we humans engage in social conflict is by sharing rumors, telling stories, pretending that we are more formidable than we are. So we should have a number of psychological defenses that makes us more resistant to manipulation.

But nonetheless, we humans believe in a range of very weird things that we do not have evidence for. So how can it be? We’ve found that when you prime people with inter-group conflict, they reach out for the stronger, more dominant individual as the leader. It wasn’t actually fear that was driving this; it was inter-group conflicts among people feeling anger. Basically, inter-group conflict is this arms race of coordination; the better-coordinated group eventually wins. The dominant leader is one way to create that [coordination], but another way is through these fringe beliefs. In the same way that you can form groups around religious beliefs to signal your group membership, you can use QAnon and other conspiracy beliefs with little basis in reality.

Ars Technica: You’re talking about tribalism, which is a double-edged sword. I think you’re saying that, evolutionarily speaking, tribes are good for survival, but this can be bad when it comes to a point where there are inter-tribal conflicts.

Michael Petersen: Exactly. There’s always conflict in politics. But the tipping point where things go wrong is when the different tribes or the different groups lose a sense of shared fate, that in the end we are in this together. We have differences of opinions, but because our fate is tied together, we need to figure out [how to work together]. What happens at that point is that you go from just conflict, to zero-sum conflict, where whatever is a benefit to them is a cost to me. Then we are in very dangerous territory.

Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP via Getty Images

Ars Technica: How does all this help explain the outbreak of violence on January 6?

Michael Petersen: Violence is a dangerous prospect. So you really need to make sure that this is the time to do it, and therefore, if you are violently disposed, then you are waiting for the right moment. A lot of the psychological machinery is operating [subconsciously]. We have people in the US who have high degrees of frustrations directed against the system, so to speak. We have been documenting that for a number of years: a construct that we call the need for chaos, which is basically this Joker syndrome where you just want to watch the world burn. There’s a substantial minority in the US who agree with very radical statements, such as “I think society should be burned to the ground. We cannot fix the problems with our social institutions. We need to tear them down and start over.” That comes with tensions that have been building up over decades, in my view. One of the factors is increasing inequality, which is not just a problem in the US, but across most Western societies.

These individuals are alone with their frustrations. What Trump does is help forge a collective identity. On the day itself, presumably, people don’t know that this is the time to go when they meet up. But you have these small coordination processes—Trump’s speech, the tension is slowly building. People go from the mindset where they say, “Well, I think something should be done,” to, “I think we should do something,” to, “I think these people also want to do something,” to what psychologists call common knowledge: “OK, now is the time. We as a collective entity want to do something and it’s now that we want to do it.”

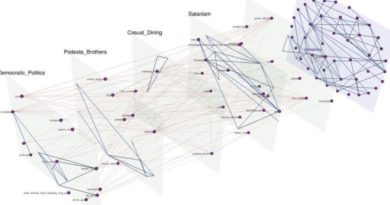

Ars Technica: Much attention has been focused on the role of social media in the spread of misinformation, and in helping violent groups better coordinate. Removing Trump and various violent right-wing groups and individuals has resulted in a staggering 73 percent decrease in the amount of misinformation circulating on social media platforms, which is encouraging. But is this a long-term solution?

Michael Petersen: What happens on social media is basically a megaphone for what happens in the offline world. It is a reflection of what happens in the offline world. So long term, we cannot steer society back on track without actually doing real reforms. On the other hand, social media does play a huge role. It acts as a coordination device. Just as radio was very important to the genocide in Rwanda, social media has been very important in stirring up sentiments in the US.

I’ve been doing quite a bit of research on what we call online political hostility. Again, it’s not the platforms themselves, it’s not that we change psychologically when we go from the offline to the online world. It’s not that nice people go crazy when they log on to Facebook and Twitter. The people who are offensive and difficult to argue with on Facebook, they are just as difficult to argue with in real life. The difference is that the audiences that you have online are much bigger, so the impact of those few antisocial individuals is larger in the online world than in the offline world. If one person is offensive in a conversation over the dinner table, then it’s just the people around the table that hear that. But if the person is offensive on Twitter, then there’s a large network of people who are exposed to that.

I’m increasingly thinking that in order to get online discussions back on track, it’s about shielding the relatively calm majority from this antisocial minority who are aggressive and using hostile tactics. One of the problems is the business model of Twitter and Facebook is really contingent on stirring up sentiments because that is what generates traffic. So there are some complications there as well; their incentive is not to keep things calm.

Eric Lee/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Ars Technica: If Trump’s rhetoric serves as a means of focusing pre-existing rage and discontent, how can we unfocus it?

Michael Petersen: That is very, very difficult. When you have forged a group, then it is very difficult to undo it again. In a sense what the US is facing is a mass process of de-radicalization, which we haven’t seen to the same extent in a modern democracy. Some of my colleagues are working with de-radicalization, and that’s not a trivial process. They are just focusing on single individuals like Islamic terrorists and so on. But this is at a much larger level.

Some lessons can be learned from the 1960s and 1970s in Europe. There was also a lot of social upheaval and violent confrontations in the street. That eventually—which is a likely scenario for the US—[evolved] into several small terrorist cells like Rote Armee Fraktion in Germany, Black September in Jordan, and so on. What took away from the mass protest was some kind of reconciliation with these groups. I think that’s potentially the most difficult part of the whole process. There are individuals who are clinging to beliefs that a lot of Americans would view as highly offensive, who have been supporting a violent attack on American democracy. But I think it’s necessary to listen to the frustrations underlying the madness and see where some reconciliation can take place—while at the same time standing firm on democratic principles.

Ars Technica: Is it enough for Trump to finally admit there was no election fraud, or would his most radical acolytes just assume that he’s been taken over by pod people, or he’s being forced to say it?

Michael Petersen: I do think that if he came out saying there was no fraud, the election was won fair and square by Biden, we should not go to the streets, and so on—that is part of breaking coordination at a mass level. So I think that could make open confrontations less likely. But the most likely scenario is Europe in the 1970s with, for example, Rote Armee Fraktion. I think the situation is extremely troublesome at least for the next five years in the US.

My sense is that what is happening in the US and other Western societies is not a difference in kind, from ethnic conflict of the worst kind, but difference in degree. It’s the same kind of psychological mechanisms that are operating, and therefore potentially some of the ways in which they have facilitated reconciliation can also be used in the US. In a way it is up to each individual to say, “Well I have two different identities. I have an identity as a son or as a daughter or as a friend or as a neighbor, and then I have my tribal identity,” as a Democrat, as a Republican, as a Trump supporter, or whatnot. It’s up to each of us to say, “Well, OK, I can try to put the tribal identities that I have to the side.”

I think you collectively need to say, “Well, we are not two tribes. We are one people with a shared faith who have all sorts of cross cutting links to each other.” It’s not easy, but I think that is crucial in the long run. It’s a very, very difficult time for the US. You should know that there’s a lot of people hoping that you will pull through because it’s a great country. In the struggle that you are facing, you have the support of a good deal of the world.

DOI: Current Opinions in Psychology, 2020. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.02.003 (About DOIs).

[ad_2]

Source link